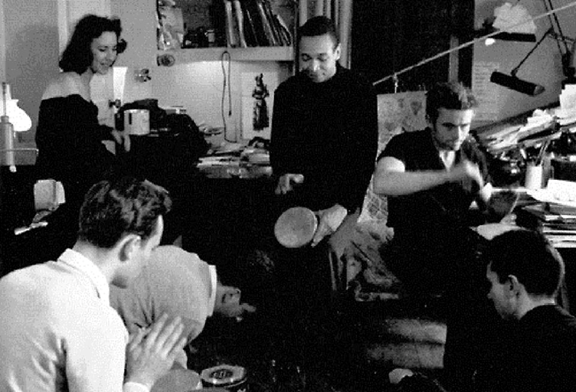

The mighty Bill Gunn

“I want to say that it is a terrible thing to be a black artist in this country — for reasons too private to expose to the arrogance of white criticism.”

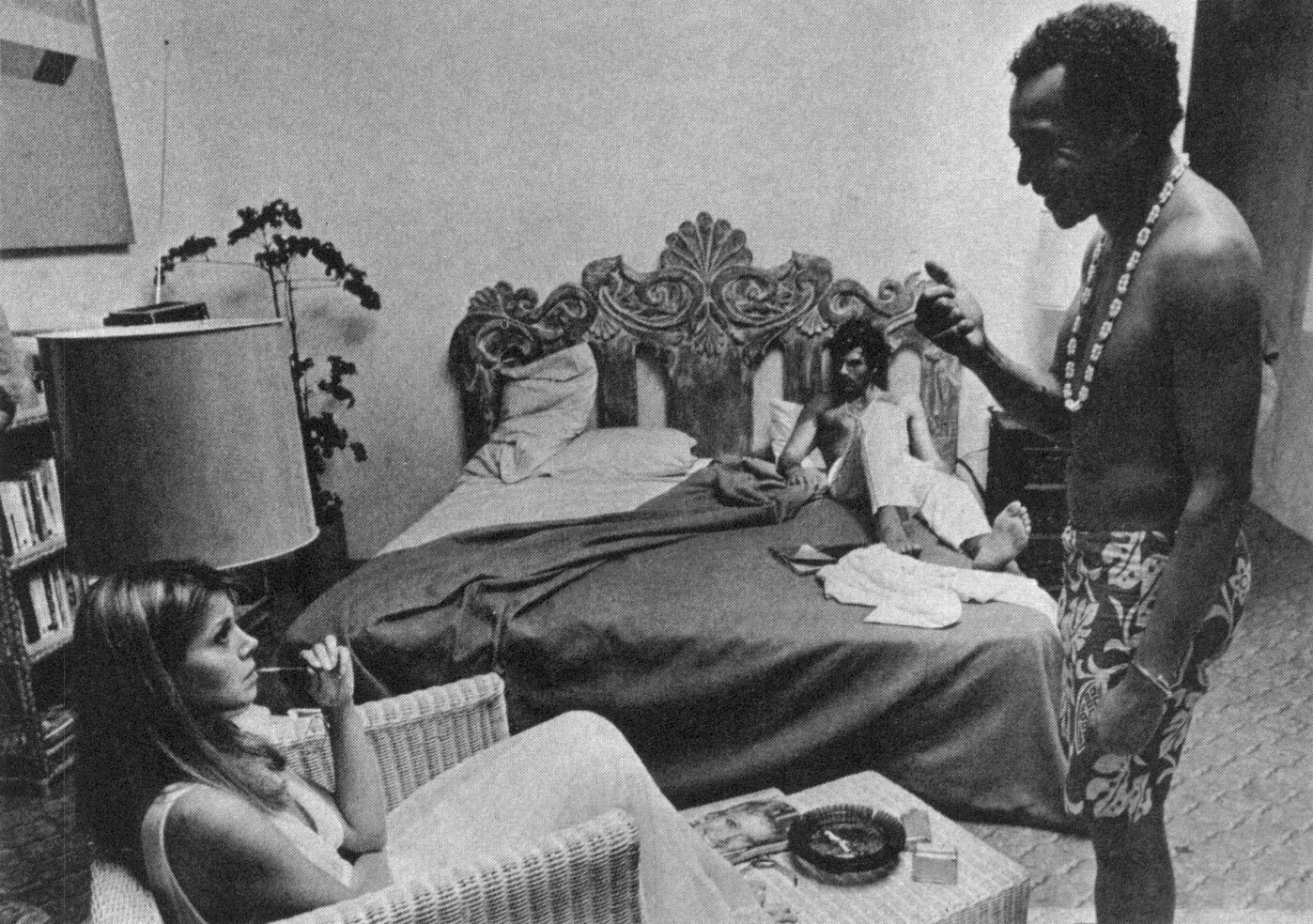

These are the words of Bill Gunn from a NY Times op-ed in response to undue negative reviews for “Ganja & Hess”. From this, you can tell that in trying to describe Bill Gunn - the man, his art, his work, his peers, his legacy - is a multi-day conversation that will go in different directions. Most people know him through 1973’s film GANJA & HESS, his quasi vampire film that was much less about the demonic and more about finding the “truth in the blood,” which as a Black American creative takes on multifarious meaning. But he was so much more.

Gunn began his career in the 1950s as a stage actor, making his Broadway debut in The Immoralist (1954) with James Dean. He wrote his first play, Marcus in the High Grass, in 1959, and wrote his first novel All the Rest Have Died in 1964. He entered the film and television world as an actor in the 1960s with roles on many series including The Fugitive (1965) and Outer Limits (1963). A prolific screenwriter, he was commissioned to write The Landlord (1970), adapted from the novel by Kristen Hunter and directed by Hal Ashby, and The Angel Levine (1970), adapted from a story by Bernard Malamud and directed by Ján Kadár. His many unproduced screenwriting credits include: Fame Game (1968) and Don’t the Moon Look Lonesome (1970). One of the first Black filmmakers to direct a film for a major Hollywood studio, Gunn made Stop! in 1970, which remains to this day unreleased by Warner Bros.

He went on to direct the masterpiece Ganja & Hess (1973) and the conceived for television series Personal Problems (1980) in collaboration with Ishmael Reed and Steve Cannon. His most notable screen role as an actor was in Kathleen Collins’ Losing Ground (1982). His teleplay Johnnas, produced for NBC, received an Emmy Award in 1972. Gunn’s theatrical productions include his plays Celebration (1967), Black Picture Show (1975), and the musical Rhinestone (1982), based on his novel Rhinestone Sharecropping (1981) a loose yet candid depiction of Gunn trying to maintain a life as a screenwriter in a racist 1970’s Hollywood system. Bill Gunn died in 1989 at the age of 59, the day before the premiere of his final play The Forbidden City at the Public Theater.

Regarding Ganja & Hess, Gunn’s partner Sam Waymon noted in a must-read June 1st Screen Slate interview: “The driving force behind the collaboration of making Ganja & Hess was independence. We're going to follow our hearts. We're going to follow our dream. We're going to follow our artistic destinies. We were going to make a film that people of color, Black folks at that time, would not have this opportunity to do again, even though the producers wanted a Black exploitation film. Obviously, we didn't make that.”

This describes Gunn to a tee, always changing the game, ultimately for the better.

Our week-long virtual screening of “Ganja & Hess” is done in partnership with Artists Space as part of TILL THEY LISTEN: BILL GUNN DIRECTS AMERICA, a comprehensive gallery exhibition and a series of public programs celebrating the life and towering, multi-faceted work of the filmmaker, playwright, novelist, and actor Bill Gunn (1934–1989) - organized by Artists Space, Hilton Als and Jake Perlin, in collaboration with Sam Waymon, Nicholas Forster, Awoye Timpo, Chiz Schultz, and Ishmael Reed. The screening also has an introduction by Curtis Caesar John, executive director of The Luminal Theater, and a post-screening panel with Dennis Leroy Kangalee, Dr. Janus Adams, Maxx Pinkins, and Zena Dixon, artists & creatives who practice are directly influenced by Gunn.